'A (Partial) Encyclopedia of the Fasces'

Review of T. Corey Brennan’s The Fasces: A History of Ancient Rome’s Most Dangerous Political Symbol (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022), Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics 32 (1), Spring/Summer 2024, 177-91.

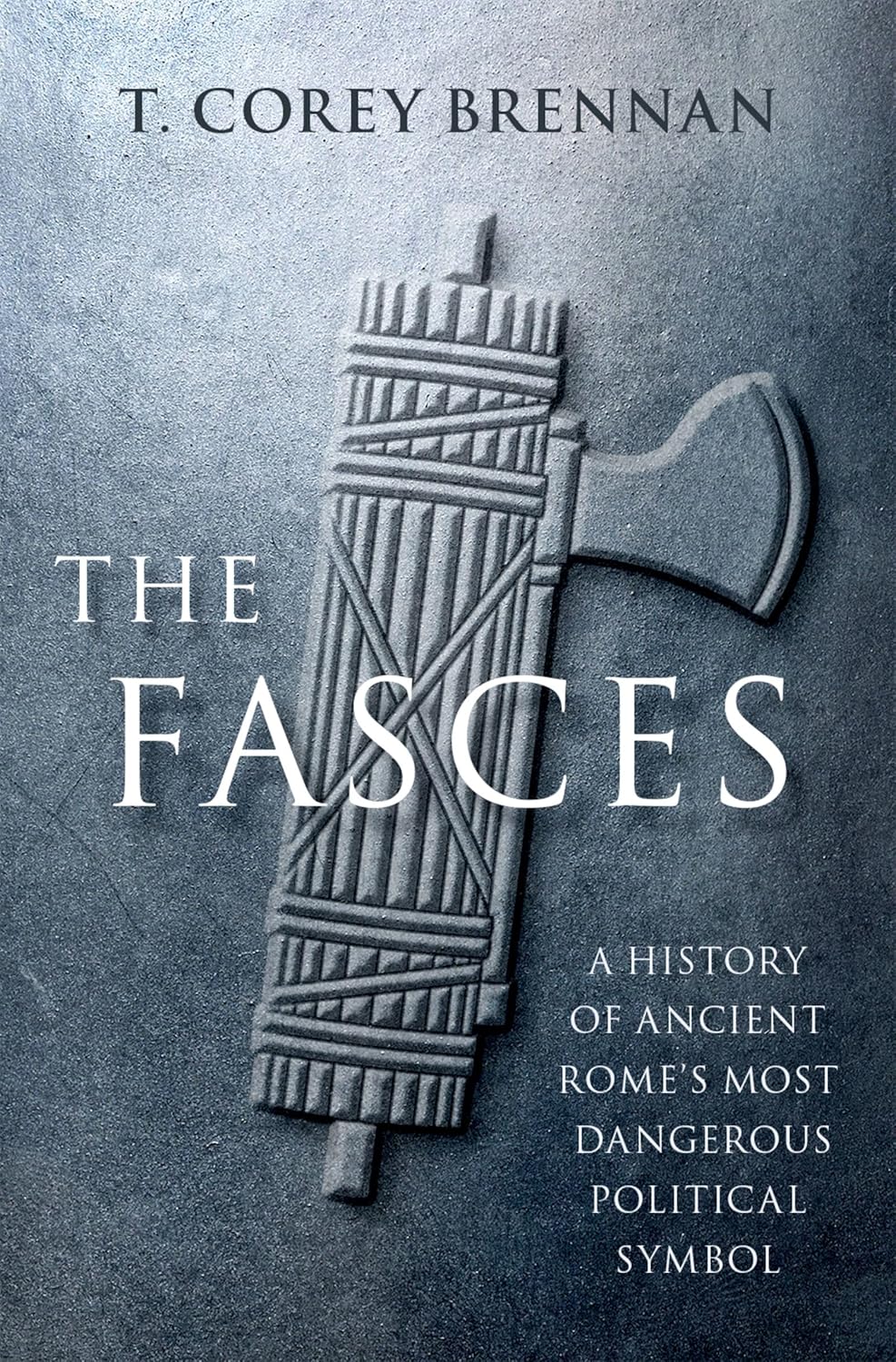

The fasces—that collection of bundled axes and wooden rods which symbolized power and capital punishment in ancient Rome—have frequently exerted a powerful hold on the Western collective imagination, long before their symbolic adoption by Mussolini led to their co-option for the term “fascist,” with all of its stark, unsavory, and brutal political connotations.

Yet the fasces’ modern association with a deadly, violent, and overbearing state authority was, in a sense, nothing completely new.

As T. Corey Brennan’s new history of the fasces as tool and symbol throughout the ages makes clear, the psychological terror inflicted on the Roman populace by the presence of the fasces, and the often brutal lictors who bore them in ceremonial pomp, was second only to the physical pain and destruction inflicted by these rods and axes once they were unbound for the purposes of instant beating or capital punishment, should the power of the magistrates entitled to them be sufficiently challenged.

Brennan’s book is at its best in its careful and painstaking collation and dissection of the available evidence from ancient Rome, beginning with the fasces’ first appearance in the grave goods found in Etruscan tombs, continuing through the age of kings, Republic, and Empire until the sixth century CE.

Though the heavily thematic structure of each chapter can inhibit diachronic analysis or the through-line of a definite narrative, the range of sources consulted (both textual and archaeological) is impressive, and those seeking an exhaustive compendium of information regarding the use and abuse of the fasces in antiquity and (to some extent) beyond will not be disappointed.

The volume is broadly divided into two halves of six chapters each, with the first half devoted to the fasces’ genesis and original use in the ancient Roman world, and the second documenting their use in iconography from the Medieval and Renaissance periods to the latter half of the twentieth century, focusing in particular on revolutionary France, post-revolutionary America, and fascist Italy (not quite the “global” history which the book’s cover promises, then, but certainly transnational).

In the pages which follow, I will begin by providing a brief sketch of the book’s content, before outlining some of the criticisms which could be levelled at its construction and execution, including the extent to which a “trade academic” book of this kind is genuinely accessible to a non-Classicist audience (a question of elitism versus accessibility).

I will then use Brennan’s work as a springboard for consideration of a broader and potentially more pressing issue: namely, the way in which his contribution mirrors broader disciplinary tendencies to eschew discussion of tendentious topics relating to the co-option of Classical antiquity by the extreme right in the present day.

*

Brennan’s first chapter, “Introduction to the Roman Fasces,” sets the scene for the chapters to come, delineating the physical and metaphorical nature of the fasces as both a “portable kit for flogging and decapitation” (p. 14), and a distinctive and tangible symbol of “imperium”—civil and military dominion.

Borne before those who held this authority by a varying number of attendants (“lictors”), who are stereotypically portrayed in our ancient sources as lowborn thugs with a penchant for violence, the presence of the fasces could inspire terror among civilians, foreigners, and citizens alike.[1]

Yet portrayals of the fasces in later ages tended to erase this aspect of their symbolic power, conflating them instead with the mere bundle of sticks signifying unity in one of Aesop’s fables; the aged protagonist demonstrating to his sons that, individually, each stick could be easily broken, yet, when tied securely together, they were unbreakable. This secondary symbolism of “strength through unity” fascinated statesmen and revolutionaries of all stripes down the centuries, from Cardinal Mazarin to Robespierre, from Lincoln to Mussolini.

The second chapter, “Origins of the Fasces,” begins the fasces’ story with discoveries of the earliest known representations of the symbol in Etruscan grave goods and Roman tombs, exploring genealogies suggested by various Roman authors, and tracing the origins of the word itself back to the Proto-Indo-European root *bhasko-, meaning bundle or band.

The subsequent chapters in this section, respectively entitled “Images of the Roman Fasces,” “The Roman Fasces in Action,” “The Roman Fasces: Limits and Discontinuities,” and “Carrying the Fasces,” then move on to explore at length the evidence—iconographic, numismatic, archaeological and textual—for the use of the fasces by magistrates, lictors, and emperors—as well as providing a wealth of thematic detail and contextualization. For instance, in 79 BCE, the dictator Lucius Cornelius Sulla’s pyre was adorned with a combustible spice-statue of a lictor constructed of frankincense and cinnamon, preceding a similar icon of the man himself (pp. 28, 38).

In fact, Sulla’s reforms in 81–80 BCE led to a veritable proliferation of fasces-bearing offices, which later reached its apogee under the Principate. Brennan also attempts to collate the scanty evidence for the lives of the lictors themselves—few are ever named in our sources, but some, especially the “proximate” lictors who acted as the bodyguard both physically closest to and often most trusted by their master, frequently formed strong relationships with those whom they were employed to protect.

The chapter on the limitations of the fasces’ power (pp. 73–92) is perhaps one of the most interesting in this section, with its depictions of fasces-smashing and popular revolt (potentially aided and abetted by the tribunes); accounts of mockery of the fasces and the inclusion of captured insignia in fake triumphs as a show of might by foreign foes who had managed to best Rome militarily; or even what Brennan dubs “fasces fraud” (p. 89)—tales of imposters arrogating magisterial authority by claiming the fasces and their bearers for themselves: an ancient Roman version of the notorious Captain of Köpenick scandal. Overall, the complex and multifaceted career of the fasces throughout Roman antiquity is reflected here in minutious (and at times somewhat abstruse) detail.

Chapters 7 and 8, “Fasces in the Medieval and Renaissance Eras” and “Early Modern and Neoclassical Fasces” (which both perhaps owe a little more to earlier work by Middeldorf-Kosegarten than the author would always like to admit) continue the iconographical catalogue of images of the fasces, with particular reference to the symbol as a representation of justice in the context of papal authority, and the art of Raphael—for instance, his work The Conversion of the Proconsul (c. 1515–16), commissioned for the Sistine Chapel by Pope Leo X.

Interpretations by Cesare Ripa and Vaenius helped to condition use of the symbol from the late sixteenth century onwards, while Cardinal Mazarin’s use of the fasces as a sort of heraldic “logo” on his coat of arms also spawned many imitators. By the mid-seventeenth century, the symbol had apparently become synonymous with strong and stable government.

Chapters 9 and 10, “Popular and Revolutionary Fasces” and “American Fasces,” then move on to the modern period, focusing on the fasces’ revolutionary symbolism in France and the United States of America.

For the French revolutionary, the fasces represented both fraternity and coercion, and, as James A. Leith put it, ‘“the citizen would also come across republican scenes and symbols in books, newspapers, letterheads, ladies’ fans, snuff-boxes, playing cards, crockery, and even furniture. Patriotic beds appeared with the posts carved in the shape of fasces or pikes topped with liberty bonnets”’ (quoted on p. 143).[2]

Focusing once again on coinage as a medium of state iconography, Brennan notes that the fasces’ revolutionary symbolism subsequently found its way to Haiti, Mexico, and Chile, as well as the short-lived Roman Republic of 1798–99.

Meanwhile, in nineteenth-century America, the fasces proliferated widely as a symbol of unity through strength in state architecture including the Lincoln Memorial, the Capitol, and war memorials such as the Godefroy Battle Monument in Baltimore. The symbol was used by both sides in the American Civil War, and could even be found adorning mid-twentieth-century state architecture, possibly due to Mussolinian inspiration.

The final two chapters, “Constructing Fasces in Mussolini’s Italy” and “Eradication of Fasces and Epilogue,” deal with the fasces’ most prominent and notorious appropriation: that of Benito Mussolini and the Italian National “Fascist” Party, who co-opted the fasces as an icon of dictatorial power. Chapter 11 focuses for the most part on episodes from the early years of Fascism, culminating in the fasces’ official adoption as Italy’s state emblem in December 1926.

Chapter 12, prior to a brief three-paragraph conclusion, then discusses the discrediting of the fasces as a symbol during and after World War II, due to its inescapably “fascist” associations, and the measures taken (more or less enthusiastically) to eradicate the symbol from Italy’s infrastructure after Mussolini’s fall.

According to Brennan, the sole instance of the incorporation of fasces in post-war public art and architecture is Alexander Stoddart’s 2001 sculpture of John Witherspoon, still to be found to this day (despite some recent protests) on the Princeton University campus.

*

As this brief sketch demonstrates, The Fasces contains a wealth of information which will undoubtedly be of great interest for those wishing to excavate the history of this fraught symbol. What it lacks, however, is a robust argument or overarching narrative framework: the monograph feels fundamentally antiquarian in its overall impulse, providing a comprehensive catalog of ancient anecdotes and iconographical depictions—an encyclopedia of uses of the fasces which often feels untethered from any broader teleology.

Especially in the first six chapters, the preponderance of short, thematic sections within each chapter, each complete unto itself but lacking any explicit connection with the preceding or following sections, makes one wonder whether a chronological approach to the ancient evidence might have been more effective and granted a greater clarity of exposition—for example, one passage on pp. 56–7 skips from 62 BCE to 69 CE to 212 CE within the space of a few lines, scarcely giving the reader time to draw breath.

In addition, the volume’s endnotes are so sparsely distributed that it is often far more difficult than it should be to find the exact reference for any given statement, including direct quotations from primary or secondary sources (see also n. 2 below).

The deployment of material within the latter half of the book can also feel rather odd at times. For example, in the chapter on Fascist Italy (pp. 178–97), little attention is devoted to official sources, or sources relating to the personal symbolic predilections of the Fascist leadership, while Anglophone press coverage of events in Italy is far more frequently cited—a bizarre choice.

Moreover, nearly seven pages (pp. 187–93) are devoted to analysis of a single event, at which the dictator was allegedly presented with a (possibly cultic) recreation of the fasces by a female supporter with potential (but not wholly recoverable) links to a group of fascist mystics. This excursus, which takes up approximately a third of the entire chapter, is then used to justify an extraordinarily sweeping statement:

“So our discussion of fasces model-making in Italy underlines how the Fascist regime, almost immediately after seizing power in October 1922, invested enormous resources into forcing the party symbol into every crevice of Italian public and private life” (p. 194).

Little evidence is adduced in support of this claim; nor does the chapter draw on any substantial amount of archival evidence or official documents—or even touch upon the manifold and fascinating ways in which the fasces were opportunistically adopted by all manner of Italian commercial enterprises.[3] The chapter’s surprising lack of in-depth consideration of the decade-and-a-half of the regime after 1926 is then justified with the following disclaimer (p. 195):

“It would take many years of work to register all the significant appearances of the fasces in Italian public building and visual and graphic art under Mussolini’s regime. Such an effort properly would take in not just all of civic and military life in Italy, but also the country’s colonies in Africa, and pieces it exported elsewhere (including the United States), e.g., for exhibitions and fairs. Such a catalog would also have to encompass permanent constructions, temporary features on preexisting structures, and wholly ephemeral items that featured the fasces. [. . .] But let us look past these complexities for the moment [. . .]”

Surely giving at least some interesting, representative examples of the uses listed here is precisely what a “global history” of the fasces should do. Plenty of recent research has touched upon such receptions of the symbol, including excellent essays by Flavia Marcello and James Fortuna.[4]

This lack of engagement with relevant recent scholarship is also evident in the section on eradication of fasces following Mussolini’s fall from power in July 1943—as Joshua Arthurs’ excellent article “Settling Accounts: Retribution, Emotion and Memory during the Fall of Mussolini” (2015) has shown, such destruction was far more widespread than Brennan gives credit for, extending not only to removal of fasces from buildings and public art, but also to the stamping underfoot of the emblem in the form of the Fascist Party badge.[5]

Such shortcomings may also be present in other chapters on which this particular reviewer possesses less expertise; at the very least, the author’s decision to eschew discussion of secondary literature in favor of “writ[ing] directly [. . .] from the primary sources” (p. 6) may not always have served him well in some of these later sections.

*

What is more, for an ostensibly “trade” book which explicitly markets itself as “essential reading for all who wish to understand how the past informs the present” (cover blurb), the volume actually assumes a great deal of pre-existing knowledge of Roman history, even within the first few pages—far more than an interested layman could necessarily boast.

As an experiment, I tested some passages out on my partner, who had more than a passing interest in Roman history in his youth, but had never studied the subject formally. Already on page three he was on unfamiliar ground when, for example, ancient authors including Horace, Statius, and Valerius Maximus are name-dropped without any contextualization or indication of their respective chronologies, and passages from Lucretius and Vergil are discussed without any delineation of the broader relevance or background of the works being cited, resulting in a potentially befuddling mélange of names and uncontextualized references for the Classically uninitiated.[6]

Fuller contextualization within the text itself, or the provision of a glossary of ancient authors and works (vel sim.) could have remedied these shortcomings; as it is, the casual reader is often expected to take the authority, chronology, and identity of many authors of ancient sources completely on trust.

This is not a book, then, which is truly accessible for a general audience, but rather one which masks its elitism with an outward veneer of accessibility and a catchy title, while demanding a degree of prior knowledge equivalent to at least an undergraduate-level Classical education.[7] This may well be in some measure the publisher’s error rather than the author’s, but if Classics as a discipline is genuinely concerned to reach out to a wider audience, then ostensibly “popular” works such as this one must acknowledge that non-Classicists may need a little more explication, sign-posting and contextualization than do those scholars and undergraduate students for whom such assumptions of knowledge are de rigueur.

However, by far the volume’s gravest shortcoming, and one which will surely leave those readers who have been assured that the book will fully elucidate “how the past informs the present” the most disappointed, is its resolute refusal to engage in any meaningful way with the use of the fasces in contemporary politics.

Despite gaining inspiration from the author’s “shock” at the use of the “Roman-style fasces” by hate-groups participating in the “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville, Virginia, in August 2017 (pp. vii, 6), the book ends its narration with the (partial) destruction of the fasces in Italy after Mussolini’s fall and the symbol’s broader discrediting, with no attempt whatsoever to analyze neo-fascist continuities—essentially leaving undiscussed the symbol’s most recent and troubling metamorphoses.

What is more, by asserting so unequivocally that “Mussolini’s totalitarian regime ended up universally—and I think permanently—discrediting the fasces as a living symbol,” and ardently asserting that the preponderance of fasces in American political architecture and iconography such as the Lincoln Memorial could not be further removed from the fascist symbolism involved in “wearing a T-shirt emblazoned with the fasces to a hate rally in 2022” (pp. 6–7), the author loses a fascinating opportunity not only to explore why the appeal to this ancient Roman paradigm may have exerted such a powerful force in all of the cases under discussion, but also to consider the ways in which the iconography of the fasces also has its roots in broader appeals to the power of Classical precedent, and the implication and imbrication of Classicizing discourse and the discipline of Classical Studies itself in these far-right appropriations of ancient Roman symbology.

As Brennan’s conclusion suggests (but does not explicate), the Anti-Defamation League’s analysis of twenty-first century hate-groups’ appropriation of the fasces points to their use in the visual language of the U.S. government as a potential point of connection and legitimation.

Hence, the author’s concluding argument (mentioned only for the first time in the book’s very last sentence, p. 217) that he hopes to combat contemporary fascists’ use of the fasces by proving that the symbol’s primary associations are far from benign seems wholly inapposite. It is highly implausible that either today’s extremists or Mussolini’s Fascists chose the fasces as a symbol because of its perceived benignity—indeed, while it may be less instantly recognizable than Nazi symbols such as the swastika, the fasces’ ancient connotations of absolute authority twinned with the threat of violence seem extremely well-suited to both Fascist and neo-fascist agendas.

Moreover, the fact that (as Brennan mentions, though with undue haste and concision) the fasces were used by American nativist parties such as the Know Nothings during the nineteenth century, and by the South prior to and during the American Civil War, suggests that there are plausible links and potential intellectual genealogies which can legitimately be drawn between the concept of the fasces as symbolic of a unity forged through the exclusion of “Others” prior to Reconstruction, and their revival in white supremacist discourse today.

By refusing to engage with any of these taxing (or even toxic) questions about the ways in which classical receptions are deeply implicated in contemporary as well as twentieth-century fascism, the book misses the opportunity to make a uniquely powerful and compelling contribution to ongoing debates, as well as demonstrating why the fasces might genuinely be considered “Ancient Rome’s most dangerous political symbol” today. The monograph therefore reveals itself to be representative more generally of the discipline’s distaste for and reluctance to confront Classics’ use to further hateful politics, portraying antiquity’s politicization in the present as a mere form of aberration which is unworthy of mention or serious scholarly consideration.

As recent research showcased by Durham University’s Institute of Advanced Study has shown, Classics as a discipline has well-honed reflexes when it comes to sweeping any hint of complicity with contemporary radical right-wing agendas under the carpet[8]—a problem which is also rife in disciplines such as Medieval or “Anglo-Saxon” studies.[9] Individual academics and disciplinary bodies alike are keen to decry far-right appropriations of antiquity as “abuses” with no historical justification or rationale.

And yet—as the groundbreaking work of scholars such as Donna Zuckerberg has shown—there are elements of the ancient world and our ancient sources which lend themselves all too easily to the legitimization of misogyny, reactionary gender ideologies, and the cultivation of Identitarian ideology and white supremacy.[10]

What is needed, now above all, is scholarship which is daring enough to expose these contexts, connections, and complicities, enabling us to comprehend more fully— and ultimately to combat—Classics’ co-option by the far right. Ignoring what is uncomfortable, or treating it with disdain or contempt for its lack of “historical accuracy,” will never be enough.

If we are to unravel the Classicizing contradictions at the heart of contemporary fascism, then we need to understand all of the continuities which underlie the fasces’ symbolic metamorphoses—and, in so doing, overwrite the gaping blanks which Brennan’s not-quite-so-comprehensive history has signally failed to fill.

—

[1] On the somewhat complex “arithmetic of the fasces,” see in particular Chapter 6, which explains in detail the number of lictors and fasces usually allotted to each type of Roman official.

[2] Unfortunately, this citation is not referenced directly (a common failing throughout the volume), however, the nearest footnote (more than a page distant) suggests that it may come from either James A. Leith, The Idea of Art as Propaganda in France (Toronto: Universi- ty of Toronto Press, 1965), or James A. Leith, Media and Revolution: Moulding a New Citizen in France during the Terror (Toronto: Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, 1968).

[3] For more on this, see Claudia Lazzaro and Roger J. Crum (eds.), Donatello among the Blackshirts: History and Modernity in the Visual Culture of Fascist Italy (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2005), especially the essay by Claudia Lazzaro, “Forging a Visible Fascist Nation: Strategies for Fusing Past and Present,” 13–31.

[4] See Flavia Marcello, “Building the Image of Power: Romanità in the Civic Architecture of Fascist Italy,” in Brill’s Companion to the Classics, Fascist Italy and Nazi Germany, ed. Helen Roche and Kyriakos Demetriou (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 325–69; James J. Fortuna, “Fascism, National Socialism, and the 1939 New York World’s Fair,” Fascism: Journal of Comparative Fascist Studies vol. 8 no. 2 (2019): 179–218.

[5] Joshua Arthurs, “Settling Accounts: Retribution, Emotion and Memory during the Fall of Mussolini,” Journal of Modern Italian Studies vol. 20 no. 5 (2015): 617–39; surprisingly, Brennan does not cite any of Arthurs’ work explicitly, including “‘Voleva essere Cesare, morì Vespasiano’: The Afterlives of Mussolini’s Rome,” Civiltà Romana: Rivista pluridisciplinare di studi su Roma antica e le sue interpretazioni, 1 (2015): 283–302, which would also have been a useful reference for this chapter.

[6] It is perhaps also worth mentioning here that the notes discussing ancient sources generally use standard abbreviations from the Oxford Classical Dictionary and Liddell and Scott’s Greek-English Lexicon (p. 219), rendering the citations opaque, bordering on incomprehensible, for anyone without some prior form of Classical education and/ or access to a Classical library.

[7] Brian Zawiski’s open access review for The Journal of Classics Teaching (2023) bears this contention out. Zawiski notes that the book may well be “too dense and scholarly to use in a wholesale manner in the secondary school classroom,” though it will certainly be “of interest to any serious student of ancient Roman history or the reception of ancient Roman symbology in the modern world.”

[8] See the papers presented at the IAS-hosted international conference on “Abusing Antiquity?” St Aidan’s College, Durham University, 14–15 November 2023, especially Curtis Dozier, “‘The Product of Twisted Minds?’ Assessing the Challenge of White Nationalist Appropriations of Greco-Roman Antiquity,” and Denise McCoskey, “From Eugenics to Genetics: The Role of (Pseudo)science in Racist Appropriations of Classical Antiquity.”

[9] See Thomas Blake, “Getting Medieval Post-Charlottesville: Medievalism and the Alt-Right,” in Far-Right Revisionism and the End of History: Alt/Histories, ed. Louie Dean Valencia-García (New York: Routledge, 2020), 179–97: 180, 188; Sierra Lomuto, “Becoming Postmedieval: The Stakes of the Global Middle Ages,” postmedieval 11 (2020): 503–12.

[10] See Donna Zuckerberg, Not All Dead White Men: Classics and Misogyny in the Digital Age (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2018), 46–50; Curtis Dozier, “Hate Groups and Greco-Roman Antiquity Online: To Rehabilitate or Reconsider?” in Far-Right Revisionism and the End of History: Alt/Histories, ed. Louie Dean Valencia-García (New York: Routledge, 2020), 249–69.