Review of Marco Hillemann and Tobias Roth (eds) 'Wilhelm Müller und der Philhellenismus'

Review of Wilhelm Müller und der Philhellenismus, edited by Marco Hillemann and Tobias Roth (Berlin: Frank & Timme, 2015), in German Quarterly 90 (4), Fall 2017, pp. 496-7.

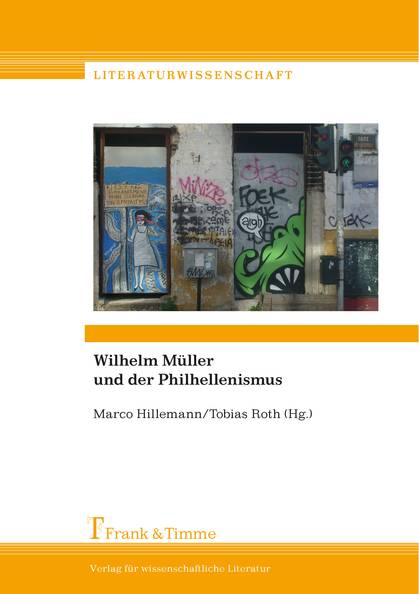

At first glance, the graffito-bedizened photograph of an Athenian street which graces this volume’s cover appears bafflingly irrelevant – only once we peer more closely does the Greek street-sign in one corner (‘HODOS MULLEROU’ or ‘Müller Street’) become apparent, giving the reader some clue as to the essay collection’s scope and intentions.

Wilhelm Müller (1794-1827) is best known, both in Germany and beyond, as the poet whose works Die schöne Müllerin and Die Winterreise were musically immortalized by Franz Schubert in the composer’s eponymous song-cycles.

However, Müller was also a highly-committed philhellene and, during the Greek War of Independence, he supported the Greek cause against the Ottomans with a plethora of poetry and prose works – most notably his Lieder der Griechen (1821-1824) – as well as with his purse. At a time when authoritarian governments throughout the German and Habsburg lands saw support for Greek national independence as potentially seditious, and perceived outspoken publicists such as Müller as dangerous elements, his publications were often subject to severe censorship, not least due to their inflammatory and highly politicized content. More than other poets of his generation, Müller tended to identify himself strongly with his Greek subjects, and many of his poems are written as if from the perspective of the country’s inhabitants, rather than from a distanced and aestheticizing external viewpoint; his style was heavily influenced by his study and translation of modern Greek folksongs.

The editors of this volume, based on the proceedings of a conference of the Wilhelm-Müller-Gesellschaft which took place in 2013, aim to illuminate some lesser-known aspects of Müller’s work and reception within this philhellenic context, decrying previous scholars’ refusal to acknowledge the blood-bespattered earnestness of the poet’s Hellenic oeuvre, treating him instead as a mere Romantic handmaiden to Schubert’s genius.

From this standpoint, the contributions by the editors themselves, Tobias Roth and Marco Hillemann, which consider Müller’s relationship with Greek antiquity and Weimar classicism on the one hand, and Müller’s non-poetic press activity in the service of the Greek cause on the other, are particularly illuminating. Stefan Lindinger and Alexandra Rassidakis also provide an interesting perspective through their analyses of works with philhellenic connotations by two contemporary female poets (Friederike Brun and Amalie von Helvig) and E. T. A. Hoffmann respectively, revealing as they do the broad spectrum of artistic responses to the Greeks’ plight which existed within the literary community at large. Further essays by Maria-Verena Leistner, Alfred Noe, and Anastasia Antonopoulou also add significantly to our knowledge of the reception of Müller’s poems in Germany, France and Greece (surprisingly, a complete translation of the Griechenlieder has never yet appeared in modern Greek).

Other contributions include a brief history of the aforementioned Athenian street, which admiring citizens named after Müller in 1884, and (as an appendix) an essay and facing translation of the Greek poet Dionysios Solomos’ Eleftheroi Poliorkimenoi (The Free Besieged, 1826-1844), in order to provide a counterpoint to Müller’s own work.

However, it has to be said that the volume’s chapters vary widely in their length, quality, and level of abstruseness. Perhaps the most bizarre indication of this tendency can be found in the peroration of a waffly essay ostensibly exploring the relationship between the Griechenlieder and Winterreise, which claims that, if Müller were alive today, he would be highly active as a blogger and social media addict, using his way with words ‘as a rap star who would challenge the conscience of his generation […and] come to the aid of the Greek nation as it again struggles to extricate itself from bondage: Economic bondage’ (p. 101).

For Müller aficionados and literary scholars, there are certainly interesting insights to be gained here – however, a longer, more wide-ranging introduction (as opposed to an eight-page preface), more rigorous editing and linking of the disparate contributions, and perhaps a final essay drawing their conclusions together, could have integrated this volume more usefully into a broader scholarly context.