Review of 'The Oxford Illustrated History of the Third Reich'

Review of The Oxford Illustrated History of the Third Reich, ed. Robert Gelatelly (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017), published in History: The Journal of the Historical Association 104, Issue 362, October 2019, 783-5.

With the editorship of a new illustrated history of the Third Reich aimed at a popular readership comes both great responsibility and great opportunity – a challenge to which Robert Gellately, one of those historians who has done most to shape the historiography of Nazi Germany in recent decades, has risen with aplomb. Not least, Gellately has shaped and framed the volume in accordance with his own approach to the hotly-contested debates over whether Hitler’s dictatorship was fundamentally coercive or consensual – privileging ideas of the National Socialist regime as a ‘dictatorial democracy’.

An introduction and ten chapters by leading international experts on the Third Reich, including Gellately himself, cover a wide range of themes, and are liberally interspersed with full-page illustrations, many of which are in full colour. Some of the contributions are informed by traditional, top-down political and economic history, such as Matthew Stibbe’s densely-packed, thorough account of ‘The Weimar Republic and the Rise of Nazism’, or Peter Hayes’ chapter on ‘The Economy’. Meanwhile, others take an Alltagsgeschichte-focused approach, informed by new trends in social and cultural history – such as Hermann Beck’s treatment of ‘The Nazi “Seizure of Power”’, or Julia S. Torrie’s wide-ranging and informative depiction of ‘The Home Front’.

In his introduction, Gellately defines four key themes which shape the volume as a whole, beginning in traditional vein with the role of the Führer himself, and then moving on to the Nazi dictatorship’s use of plebiscites and elections (a topic which also enjoys extensive coverage in Hedwig Richter and Ralf Jessen’s highly illuminating chapter on ‘Elections, Plebiscites and Festivals’). In this connection, Gellately recalls a Social Democrat’s report from Munich in March 1936, observing a rally concerning the plebiscite over the remilitarisation of the Rhineland: ‘“People can be made to sing, but they cannot be made to sing with such enthusiasm”’ – a statement which can arguably be taken as a leitmotif of Gellately’s approach to the Third Reich in general, as well as to this volume in particular. The quartet of themes is completed by consideration of Nazism’s social vision – the promise offered by the ideal of the Nazified national/racial community, the Volksgemeinschaft – and War and Empire; Gellately notes that the dictatorship’s plans for the conquest of an empire stretching far beyond the Urals, including the deliberate starvation and enslavement of millions, continued to grow in scale even once the tide of the Second World War had inexorably turned for the worse.

In terms of capturing the texture of everyday life under the Nazi dictatorship in a compelling and original fashion, the contributions by Beck, Richter and Jessen, and Torrie stand out particularly. The violence balanced by the allure of Gleichschaltung (“coordination” with the regime); the mingling of a festival spirit with the most hateful forms of pillorying, fraud and oppression on so-called election days; the powerful mixture of mobilisation and modernity, and the constant interconnections and porous boundaries between the battle front and the home front during a time of total war, are all delineated here with nuance and dedication.

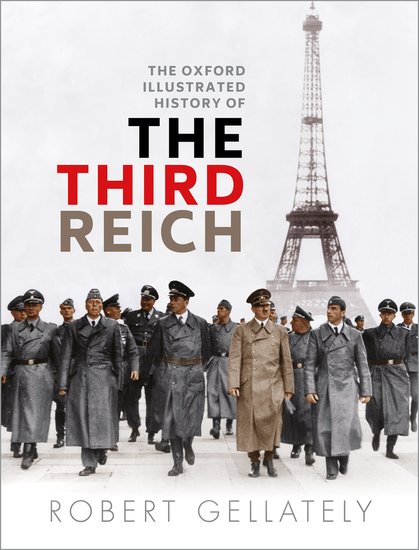

Perhaps it is no coincidence, however, that two of the most powerful contributions in the volume deal with visual imagery; namely, Jonathan Petropoulos’ chapter on ‘Architecture and the Arts’, and David Crew’s chapter on ‘Photography and Cinema’ – which follows an imaginary Berliner’s daily routine, chronicling their encounters with the regime’s ubiquitous forms of visual propaganda. For it is one of the book’s greatest strengths that it is – as befits an ‘illustrated’ history – lavishly supplied with both black-and-white and full colour illustrations. Some of these, as on pp. 10 and 12, include contemporary colour photographs or stills from cinema footage; a form of image which still has the power to shock, given the vividness and vitality which it lends to an era which often appears monochrome in the imagination; a visual act of distancing. Of course, many of the images deployed here are familiar – propaganda posters and photographs predominate – yet these are cogent, and tellingly incorporated into the text. The only disappointment on this score is the lack of information regarding the pictures’ provenance and genesis – the captions in the text often leave the reader none the wiser, and the only acknowledgements supplied are the copyright credits. Similarly, the fact that no citations are included, merely lists of bibliographical items appended to each chapter for ‘further reading’, is somewhat frustrating, since it does not give the reader the wherewithal to follow up on specific points, claims or sources.

All in all, however, this is a volume which has much to recommend it to the scholar, the student and the layman alike, and it will doubtless find a home on numerous sitting-room bookshelves (if not coffee tables) for many years to come.